A Storm We Won’t Fully Escape: One Generation’s View of the Fourth Turning

Born on the border between Boomers and Gen X, I’ve watched America shift from the confident post-war era into today’s turbulence. This essay explores Neil Howe’s Fourth Turning framework—not as prophecy, but as a useful way to understand why the country feels like it’s entering a decisive crisis. I look at how we got here, how Millennials will likely be the ones who rebuild what comes next, and what that means for those of us in the middle who benefited from the old order and may feel the financial and social strain of the transition ahead. It’s not a prediction—just an honest, thought-provoking look at the decade in front of us and our place within it.

Living Through the Fourth Turning

Thoughts from Someone Stuck Between the Boomers and Gen X

I was born in 1963, which means I’m in that no-man’s-land between Baby Boomers and Gen X. Too young to be a true Boomer, too old to be a real Gen-Xer. I remember rotary phones and three TV channels, but I also built a career in a global, digital economy and adapted to all the technology that came with it.

In other words, I’ve had a front-row seat for the long slide from the “America still basically works” era into whatever we’re living through now.

Over the past few years I’ve been drawn to Neil Howe’s “Fourth Turning” framework as a way to make sense of this mess. Not because I think it’s a scientific law of history—it isn’t—but because it’s a surprisingly useful lens. It helps me understand why the country feels the way it does, why the arguments we’re having are so intense, and why my generation is unlikely to be the one that fixes it.

If Howe is right, we’re not just in a rough patch. We’re living through the crisis phase of a bigger historical cycle. And as someone in his early 60s, I’m old enough to be affected by the fallout and just young enough to know I’ll still be around to deal with it.

This essay is my attempt to explain Howe’s framework in normal language, say why I think it has merit, acknowledge its critics, and be honest about the uncomfortable part: if this plays out the way he expects, people my age are likely to take it on the chin financially so that our kids’ generation can rebuild something that works better for them.

I’m not writing this to preach or recruit anyone into a cult of historical cycles. I’m writing it so my friends can think about what may be coming—and what it might mean for us, our kids, and our retirement accounts.

The Short Version of the Fourth Turning

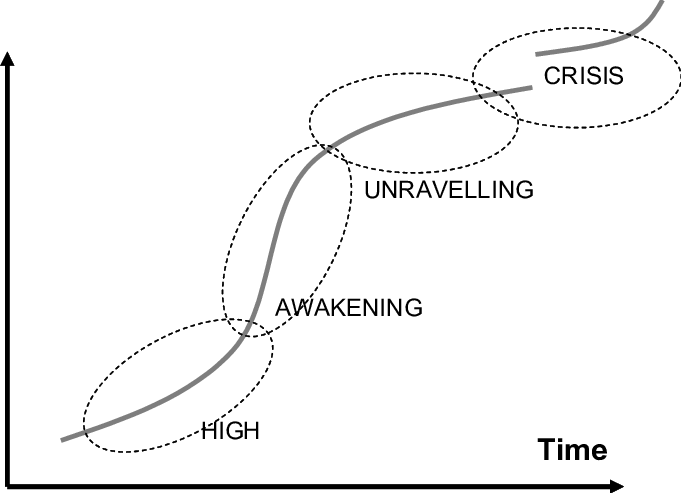

Howe’s basic idea is simple:

History doesn’t move in a straight line; it tends to move in long cycles of about 80–90 years, roughly a long human life.

Each cycle, which he calls a saeculum, has four “seasons”, each lasting about 20 years:

High – Institutions are strong, society is confident, individualism is more subdued. Think 1950s.

Awakening – Spiritual, cultural, and social revolts. Think late 1960s and 1970s.

Unraveling – Institutions weaken, individualism and cynicism grow. Think 1980s–1990s.

Crisis (Fourth Turning) – The whole system comes under stress: financial, political, social, sometimes military. Institutions are torn down and rebuilt.

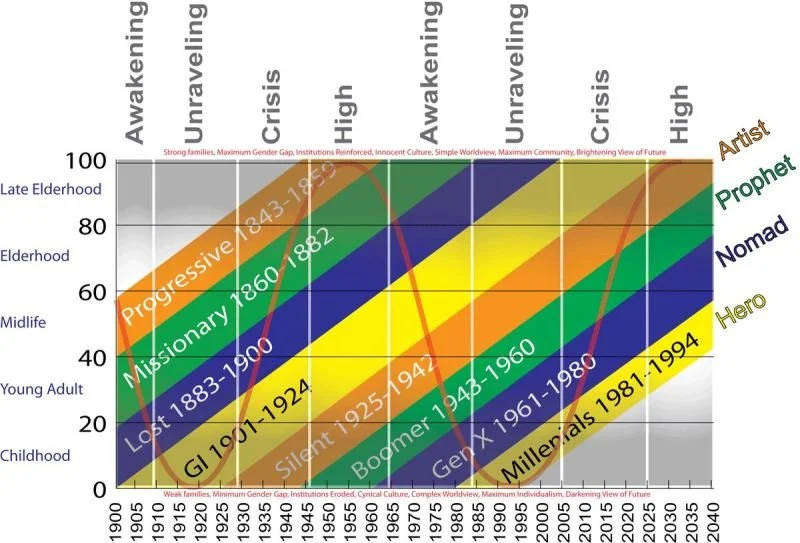

He then maps these seasons to generations:

Boomers: moralizing “Prophets”

Gen X: skeptical “Nomads”

Millennials: civic “Heroes”

Gen Z: more cautious, adaptive “Artists”

Each generation grows up in a different environment and then behaves in somewhat predictable ways later in life. As they age, they push society toward certain moods and choices.

According to Howe, America has gone through several of these cycles. The three most recent Fourth Turnings were:

The Revolutionary era

The Civil War era

The Great Depression and World War II era

You don’t have to buy every detail to see the broad pattern: roughly every 80–90 years, we hit an existential crisis where the old way of doing things simply can’t go on. The system breaks, gets rebuilt, and a new “normal” emerges on the other side.

In his newer work, Howe argues that our current Fourth Turning started around the 2008 financial crisis and probably runs into the early–mid 2030s. That would put us right smack in the middle act now.

Do I think this is “proven science”? No.

Do I think it’s a surprisingly useful framework for understanding the last 15–20 years? Yes, I do.

Why This Matters to Me (and Probably to You)

At my age, this isn’t an abstract intellectual exercise. It’s personal.

I’m old enough to have benefited from the long boom: decades of economic growth, inflated asset prices, and the tailwinds of the post-World War II order. I worked hard, made responsible decisions, and I’m fortunate: I’m not in the group that’s already getting hammered financially.

But if Howe is right, the crisis phase we’re in now is about re-pricing and re-balancing a system that has drifted out of whack. That likely means:

Debts that can’t all be paid back on the original terms

Promises (pensions, entitlements, benefits) that can’t all be honored

Assets (homes, stocks, bonds, businesses) that may not behave like they did in the “good old days”

And it probably means something else: the generation that has been losing out (Millennials, mainly) will eventually get the political leverage to rewrite the rules.

That’s the part that worries me—not because I think they’re wrong to demand change, but because I know where I sit in the food chain.

If you’re around my age, we’re in an awkward position:

We’re too young to be completely insulated by “I’ve already got mine, nothing can touch me.”

We’re too old to get a full reset under a new system that’s designed for people in their 30s and 40s.

So when I read Howe, I don’t just see an interesting historical pattern. I see a flashing sign:

“Heads up. This transition is not going to be financially painless for people like you.”

Millennials as the Rebuilders, Not Us

One of Howe’s most important points is this: the generation that leads you into a crisis is rarely the generation that leads you out of it.

That stings a bit for those of us on the Boom/Gen-X cusp who still like to think we’re running the show.

Boomers (and the older half of my micro-cohort) have dominated leadership for decades—in business, politics, media, academia. Gen X has been the small, skeptical middle child trying to keep the wheels on. And what have we collectively produced?

A heavily indebted government

A stretched global order

A polarized electorate

A generation of young adults who can’t afford the same life scripts we grew up expecting

We can debate who’s to blame and how much of that is “our fault.” But at some point, if you’re honest, you have to admit: we’re not going to be the ones who design the next system.

Millennials will.

They’re the ones coming into full power over the next decade. They’re the ones who will eventually control the levers of government, corporations, and cultural institutions. And given their experiences—student debt, housing costs, job precarity, social media chaos, two big economic shocks before age 35—they’re not going to be content with cosmetic tweaks.

If Howe’s framework is right, they will push for:

Stronger, more activist institutions (“somebody do something”)

More collective solutions (healthcare, education, social insurance, climate, infrastructure)

Less tolerance for “you’re on your own” economics

From their point of view, that’s rational. From ours, it may feel like the bill for the last 40 years of comfort, tax cuts, asset inflation, and institutional decay finally showing up on the table.

And here’s where I land: that tension is exactly why I take Howe’s framework seriously. It lines up not just with the headlines but with the generational mood I see all around me.

Why I Don’t Treat This as Gospel

Now for the important caveat: I do not think the Fourth Turning is some sort of cosmic law.

You can’t plug a date into a formula and get “civil war in 2028” or “currency reset in 2031.” Real life is messier than that.

The criticisms are valid:

It’s not a rigorous scientific theory. It’s pattern recognition.

The categories (Prophet, Nomad, Hero, Artist) are broad and fuzzy.

The dating of past turnings is somewhat subjective; if you slide the dates, the pattern still “works.”

It can be abused by people who want to force a crisis or justify extreme actions because “history demands it.”

I’ve read some of the people who call it “astrology for politics.” I don’t think that’s entirely fair, but I understand the reaction. Anytime you draw sweeping lines through history, you’re going to smooth over a lot of complexity and coincidence.

So why do I still give it weight?

Because even if you strip away the archetypes and the poetic language, the core observations are hard to ignore:

Democratic societies tend to borrow from the future until the future pushes back.

Institutions lose legitimacy in cycles. Trust isn’t a straight line; it decays, breaks, and sometimes gets rebuilt.

Generations who grow up in different circumstances really do see the world differently and vote accordingly.

Every 70–90 years or so, the U.S. has gone through a system-defining crisis that rewrote the rules.

To me, the Fourth Turning is not a prophecy. It’s a framework that says:

“These are the kinds of pressures that build up over a long cycle. If you ignore them, don’t be surprised when something gives.”

That’s how I use it. Not as a script, but as a warning label.

What This Might Mean for Us Between Boomer and Gen X

So if you’re in my general age bracket, what does all this imply?

A few uncomfortable possibilities:

Our retirement math may be more fragile than we like to admit.

If the crisis involves higher inflation, changing tax regimes, or stressed entitlement systems, the “just keep doing what we’re doing and it’ll all work out” plan may not hold.We may be asked—explicitly or implicitly—to give something back.

That could mean higher taxes, reduced benefits, means-testing, or policies that prioritize younger generations’ needs over ours.Political battles will increasingly be about the inter-generational social contract.

Who pays, who benefits, who sacrifices. We’re not going to be sitting in the cheap seats for that argument; we’ll be in the middle of it.Emotionally, we’ll be tempted to dig in our heels.

The natural reaction is to say, “I played by the rules. You can’t change them now.”

I get that. I feel it. But part of taking Howe’s framework seriously is acknowledging that the rules always change in a crisis. They have before. They will again.

That doesn’t mean we have to roll over or agree with every plan that gets floated. It does mean we shouldn’t be shocked when Millennials act like the country belongs to them—because, increasingly, it does.

Why I’m Still Cautiously Optimistic

If this all sounds grim, let me end on the part of Howe I actually find encouraging.

In previous Fourth Turnings, the crisis period was awful—but the destination on the other side was better than what came before:

The Revolutionary crisis produced a functioning republic.

The Civil War crisis ended slavery and redefined the Union.

The Great Depression/World War II crisis produced the post-war order that, for all its flaws, delivered broad prosperity for decades.

The people living through those storms didn’t enjoy it. A lot of them didn’t make it. The sacrifices were real. But the long-term trajectory after each crisis turned upward.

So when I look ahead, I imagine something like this:

We struggle through the 2020s and early 2030s with financial, political, and social stress.

The old order continues to fray until some combination of elections, legislation, reforms, and maybe crises forces a reset.

Millennials—with Gen Z in tow—inch their way into full control and begin building the next “normal”: different institutions, different compromises, a different understanding of what the American promise looks like.

We may not like all of it. We may lose some things we value. We will almost certainly lose some money along the way.

But if the pattern holds, our kids and grandkids could end up living in a more coherent, stable, and functional society than the one we’re handing them right now. And if that’s the trade—our generation absorbing some of the adjustment so they can build something livable—then maybe that’s not the worst legacy.

How to Recognize the Stages of a Fourth Turning—and How to Spot the Leader Who Signals It’s Ending

Howe says every Fourth Turning follows a basic rhythm: a shock, a rally, a decisive struggle, and a rebuild. The specifics change, but the pattern has repeated often enough in American history to pay attention. One other piece matters too: the emergence of a unifying elder leader—the Gray Champion—who helps pull the nation through the hardest part of the storm.

Here’s the short version of how to recognize the stages, and the kind of leader to watch for.

1. The Catalyst

The moment the old system cracks and confidence breaks.

For us, that was 2008—the financial meltdown that ended the “everything’s fine” era and pushed the country into long-term instability.

2. The Regeneracy

The country realizes drifting isn’t an option anymore.

People demand direction, purpose, and big solutions—even if they disagree on which ones. Rising populism, rising turnout, and rising frustration mark this phase. We’ve been stuck in this energy for most of the last decade.

3. The Consolidation

Eventually, the country aligns behind a shared direction—either because of a crisis too big to ignore or a leader who can finally unify competing tribes.

This is where the Gray Champion comes in.

The Gray Champion: Howe’s Signal That the Tide Is Turning

In every past crisis, an elder moral leader has emerged—someone from the older “prophet” generation—who doesn’t divide or blame, but binds the country together at the moment of greatest danger.

The Gray Champion isn’t about charisma or party politics. It’s about character.

The traits Howe outlines:

A unifier, not a divider. Someone who can speak across factions and be heard by all of them.

Calming, not inflaming. They quiet the culture-war screaming and turn down the national temperature.

Moral clarity without moral bullying. They articulate what’s right without demonizing half the country.

Responsibility over resentment. They don’t point fingers; they invoke shared duty.

Purpose over politics. The message shifts from “who’s to blame” to “what must we build.”

Able to rally Millennials. Howe is clear: the younger generation does the actual heavy lifting. The Gray Champion provides the spark and the direction.

This figure can be a president—but doesn’t have to be. Past examples include Lincoln and FDR, but also elder statesmen and public figures who rose above their own party and moment.

The practical takeaway: if you want to know when we’re moving from chaos to resolution, look for the first leader who pulls the country together instead of tearing it further apart.

4. The Climax

The decisive showdown—the moment the old order finally collapses and the new one is shaped.

This phase is dramatic, dangerous, and clarifying. The Gray Champion’s presence matters most here: their leadership can steer the conflict toward renewal rather than ruin.

5. The Resolution

This is how you know the Fourth Turning is ending:

The issues that drove the crisis are actually resolved, not just argued about.

A new institutional order takes shape—more coherent, more functional.

Millennials step visibly into their role as the builders and stewards of the new era.

The country feels pulled in one direction again, not fifty.

Trust—slowly, gradually—returns.

That’s when winter turns to spring.

In short:

We’ll know we’re past the worst of the Fourth Turning when two things happen:

(1) A leader emerges who unifies rather than divides, and

(2) The country begins acting with shared purpose instead of competing panic.

When those two forces line up, the rebuild begins—and the next American era takes shape.

Why I’m Writing This at All

I’m not trying to scare anyone, and I’m certainly not auditioning to be an armchair revolutionary. I’m writing this because if we really are in a Fourth Turning, then it’s not enough to simply brace for the storm—we need to understand how we eventually get out of it.

Part of that is recognizing that a crisis like this has a shape: systems break, generations shift roles, and eventually a leader emerges who helps pull the country toward resolution instead of deeper division. Howe calls this the “Gray Champion”—not a divider, not a blamer, but someone who quiets the noise, rallies the country, and gives the younger generation the direction they need to rebuild.

And here’s the important point: we haven’t seen that person yet.

Not in politics, not in business, not in culture. Which means we need to be watching closely—because when that type of leader finally appears, it’s one of the clearest signs that we’re turning the corner and moving toward the other side of this.

If Howe’s framework has any value for people our age, it’s that it reminds us this moment isn’t just “politics gone crazy.” It’s a pattern of stress and renewal that the country has lived through before. You don’t need to buy every detail—or remember which generation is the Prophet or the Hero—to see that something larger is happening.

My goal here is simple: to give all of us a lens to think about the next 10–15 years with clearer eyes, and to recognize that while our generation helped shape the world that’s now cracking, it will be our kids’ generation that ultimately shapes what comes next.

We’re still part of the story—but not the main characters in this final act. They are. And whether we agree with every choice they make or not, we’re all going to be here to watch the next chapter unfold.