The Forgotten Beginnings of St. Andrews

This history covers the period from the early Spanish explorations of the 1500s through the year 1922. It’s based on G.M. West’s century-old work, St. Andrews, Florida (1922) written at a time when much of the area's early story was already fading from memory. Everything that happened after 1922—including modern St. Andrews, the marina era, hurricanes, and today’s revival—is outside the scope of the original source and isn’t covered in the story below.

How a Quiet Florida Bay Became a Crossroads of Empires, Storms, Dreams & Disasters

If you stand on the St. Andrews shoreline today and watch the pelicans glide low, the boats hum across the bay, and the sunset settle in that soft Florida way, it’s hard to imagine just how many times this peaceful place has been claimed, abandoned, reshaped, destroyed, and rediscovered. But long before Panama City, marinas, or tourists with beach chairs, St. Andrews Bay was a blank spot on a map that kept calling explorers, settlers, soldiers, surveyors, and dreamers.

G.M. West’s St. Andrews, Florida (1922) isn’t a modern history book. It’s a treasure hunt: a determined man digging through old maps, forgotten land records, naval orders, early newspapers, and half-lost stories to piece together what happened here before we ever showed up with condos and fishing rods. What emerges is a sweeping story that’s sometimes rough, sometimes poetic. A story of a bay that refused to stay quiet.

Here’s that story in the plain language of today.

A Name Written by the First Europeans Who Saw It

The earliest Europeans to scan this coast were Spanish explorers sailing across the Gulf in the 1500s. Their habit was simple: when you spot a new bay, name it after the saint whose feast day it happened to be. That’s how our bay likely became Bahía de San Andrés, and why this coastline is dotted with saint names from St. Marks to St. Joseph.

The name stuck. Long after Spain lost control, long after the British left, long after the Civil War burned St. Andrews to the ground—the name remained a constant when everything else changed.

A Coastline Reshaped by Wind and Water

If you think the geography of St. Andrews Bay has always looked like it does now, think again.

By comparing maps from 1764, 1825, and 1855, West shows how this coastline was dramatically rearranged by violent storms:

A single barrier island shattered into several.

New passes were carved.

Entire sandy spits disappeared.

Islands like “Sand Island” appeared and vanished in a single generation.

This place has always been alive—shifting, breaking, rebuilding.

Early Settlers and the Fields That Became Rosemary

The first English settlers arrived after 1763, when Britain gained the Floridas. They planted homesteads along the bay, cleared fields, and even discovered that grapes grew beautifully here—so beautifully, in fact, the French worried the colonies might compete with their vineyards.

Then they were gone.

Only rosemary now grows where their fields once lay, a bittersweet reminder West quotes Shakespeare to capture:

“Rosemary, that’s for remembrance.”

Spanish, English, Americans—and Nobody Stayed

One of the strangest facts West uncovered is this:

for all the activity here between 1500 and 1800, no descendants remain.

Spain controlled the bay.

Then England.

Then Spain again.

Each time, foreign powers pulled settlers in, then pulled them back out. By the early 1800s, the bay was a blank page once again.

The land waited—quiet, empty, beautiful.

John Clark & the First Real Attempt at a Town

The modern story of St. Andrews begins around 1827 with John Clark, a Georgian whose portrait appears early in the book. He wasn’t the first human to see this land, but he was the first to stick around long enough to matter to its future.

Clark and others:

petitioned for a customs district,

surveyed land,

attracted early commerce,

and pushed for a canal linking St. Andrews Bay to the Chipola and Apalachicola Rivers.

These ambitions were big—maybe too big—but they left the first real fingerprints of a community.

Storms, Surveys & the Struggle to Be Seen

Throughout the 1800s, surveyors like Gauld and Williams kept returning to the bay, trying to make sense of its shifting geography and its potential. Maps showed proposed canals, railroads, sawmills, boat landings, and even a chartered St. Andrews College (which never happened).

The federal government reserved large swaths of shoreline for live oak harvesting—the prized wood used for shipbuilding. A sawmill was built on Watson’s Bayou, and a handful of fishermen salted their catches for inland planters.

A town was slowly taking shape.

Civil War Flames & the Long Road Back

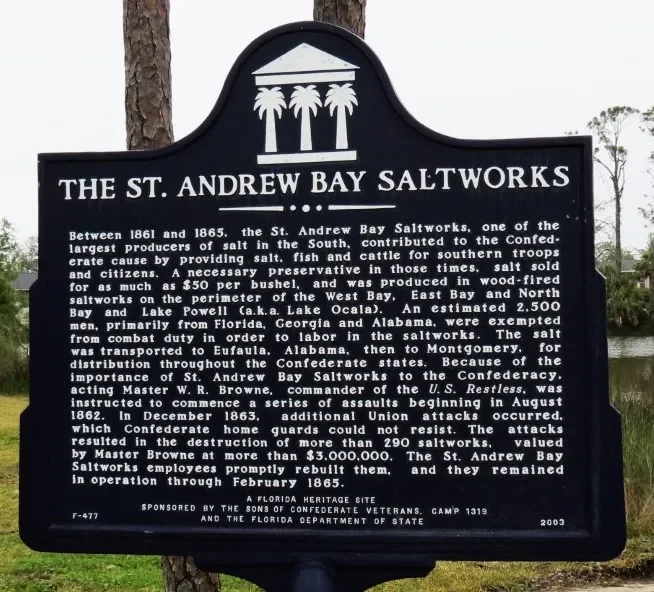

When the Civil War arrived, St. Andrews found itself under the watchful eye of the Union Navy. West includes the official naval orders documenting the blockade, the seizing of cotton schooners, and ultimately the destruction of the settlement.

By 1863, Old St. Andrews was burned and abandoned.

Recovery was slow.

The census numbers barely budged.

Life moved inland, not toward the coast.

But the bay had one more rebirth left in it.

The Great St. Andrews Boom (1885–1888)

Enter the Cincinnati Company, a land-and-railroad outfit with big dreams and even bigger marketing budgets. They advertised St. Andrews as the next great Southern paradise:

350,000 promotional booklets mailed

glowing descriptions

easy land payments

a platted grid of tiny lots (too small for real farms)

The good news?

People came—lots of them.

The bad news?

Most left when they realized tiny lots and big dreams don’t always mix.

But the boom left St. Andrews with new streets, new buildings, and a renewed identity.

A Port of Entry Again

By 1911, St. Andrews finally regained federal recognition as a sub-port of entry, giving the area a boost in legitimacy and economic opportunity as the 20th century arrived.

And that’s roughly where West leaves the story—on the edge of modernity.

Why This History Still Matters

West’s book makes it clear: St. Andrews has never been a place that just “happened.” It’s a place people have kept rediscovering—Spanish explorers, English settlers, American pioneers, Civil War blockaders, post-war families, Northern investors, and eventually the folks who built the St. Andrews we know today.

It’s a place shaped by:

storms

ambition

abandonment

reinvention

and endless natural beauty

Every time the bay was forgotten, someone else showed up and said, “Look at this place… how is the rest of the world not seeing this?”

You could say we’re just the latest in a long line of rediscoverers.

And judging from the sunsets, the fishing piers, the parks, the community, the music, and the stubborn local pride—we’re not planning on giving it up anytime soon.